Seagrass blues

29 June 2011, by Andrew J Wight, Cosmos Online

Broken sea grasses float over a degraded coral reef

The world's seagrass meadows are under threat and with them, species diversity and economic activity - but there's another reason to care about their fate.

SQUISHY AND LARGELY hidden, seagrass meadows may have a more difficult time grabbing headlines than their coral reef cousins, but researchers are now finding that preserving these forests of the sea may have a vital role in the climate change puzzle.

If you were to look out over Port Phillip Bay as it laps against the Melbourne shoreline, you are close to some of the most diverse marine habitats on the planet - and that's just a small part of Australia's seagrass meadows.

Along our 32,000km coastline, there's some 90,000 square kilometres of sea grass meadows, each made up of individual seagrass plants: mainly large, leafy and sun-loving.

Out of the 72 known seagrass species, Australia has 26 of them, some of which are found nowhere else on Earth, such as the endangered Posidonia sinuosa of Western Australia.

Seagrass meadows provide homes, food and nurseries for many marine creatures, in particular serving as feeding grounds for dugongs and western rock lobsters (Panulirus Cygnus) and breeding grounds for many commercially important fish species.

They are also important for water quality, filtering water and serving as an indicator of the health of the marine ecosystem, but the health of the meadows themselves has become of increasing concern.

In a recent study, 15 of the 72 known species of seagrasses were listed as 'Endangered', 'Vulnerable' or 'Near Threatened' on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List.

Seagrass researcher at the University of Technology Sydney, Peter Macreadie says there are multiple factors that make seagrass vulnerable, but the biggest threat is the creation of anoxic dead zones by algal blooms.

"Seagrass are plants that grow on the seafloor, so when nutrient runoff is taken up by the algae, the algae become dense and it blocks the sunlight from reaching the seagrass."

There is also direct damage done by humans via dredging or by boat propellers. If some plants are disturbed in the middle of a meadow, the 'hole' will actually get bigger and bigger, eating away the meadow from the inside. "We know we've lost 30% of the world's sea grasses already," says Macreadie.

Many seagrass scientists are now concerned about changes in water temperature caused by the apparent effects of climate change, he added. "Seagrass is changing its range and distribution, but they can only tolerate a certain set of temperatures."

Paradoxically, seagrass may be part of the solution to this threat.

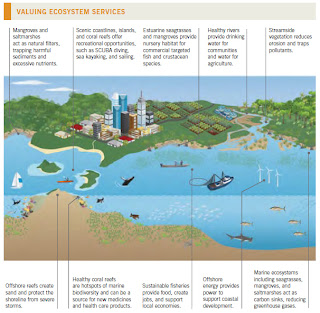

"When we think about carbon sinks, most of us think about tropical rainforest like the Amazon," says Macreadie. "But seagrasses, mangroves and salt marshes cover 1% of the seafloor, but are estimated to sequester 70% of the ocean's carbon."

The first Blue Carbon report came out in 2010 and detailed how coastal ecosystems, including seagrass sequester carbon. According to Macreadie, it is estimated that seagrass beds can store for carbon for thousands of years, as opposed to the dozens of years of terrestrial plants.

"Like any plant, seagrasses go through seasons and left undisturbed, a typical plant could last for years and years. But unlike, say a rainforest, when seagrass shed their leaves or die, the leaves, roots and rhizomes don't decompose readily. That litter gets buried beneath the seagrass meadows and layers start to form."

Research groups from Europe have found that this layer of fibrous material gets locked away in deep sediments, and the amount of carbon sequestered can be estimated.

"We can age these cores and we're finding seagrasses up to 6m deep stored for thousands of years," said Macreadie.

It is hoped that by showing the capacity of seagrass to store carbon, they will be better candidates for funding and awareness in the same way that forests are conserved for their biodiversity and carbon storage capacity. There are, however, some hurdles to overcome.

The combined threat of increased pollution, increased population pressures from humans and their slow regeneration time means world is struggling to hold on to the seagrass it has, let alone expand their current range.

Past director of the University of Western Australia's Oceans Institute, Gary Kendrick says restoration can get expensive.

"I've been working on a five-year restoration project and the chances of full recovery are still slim, as restoration is high risk and high expenditure. The seagrass restoration itself can cost anywhere from AU$8,000 a hectare to hundreds of thousands of dollars per hectare," he says.

"There are studies of a field that cost $1 million a hectare to restore. That's about ten times what it costs to restore a forest. It is much easier to conserve the seagrass habitats we already have in the first place, rather than trying to restore them after the fact. In Australia you can count the research groups on one hand, but the awareness of the importance of seagrass is growing."

What Kendrick hopes to do in the next five years is to bring together Australian groups in a research centre. "Rehabilitation is going to cost, so we'll look at what are the big threats to the seagrass and how do we best counter them?"

Mick Keough, at the Department of Zoology at the University of Melbourne, who has recently received funding to identify key seagrass habitats in Melbourne's Port Phillip Bay says the situation is improving for seagrass in Australia. "Some state governments, Western Australia and New South Wales in particular have strong emphasis on protection of seagrass."

But he adds that while seagrasses are seen as important by government, public perception is a real problem. "They aren't as charismatic as the reefs, but their role in nutrient cycles are a really important part of the ecosystem. I don't think anyone sees them as a pest anymore, but the don't have the same passion as they might for the barrier reef."

Researchers need to understand how disturbances affect seagrass habitats and the processes that are important for their recovery, Keough adds.

"Within the Bay, many species are found predominantly in seagrass meadows, and some species actually rely on seagrasses for survival in part of their life cycle," he said.

So when you step on that squishy piece of seagrass on the beach, don't curse: without these humble plants, our seas would be less rich with life, our water more turbid and our climate more turbulent.